We should rethink the systems we use to commercialize science

On emerging models for organizing technoscience, and a proposal for Directed Innovation Institutes.

This is the third of three essays in which I use concepts from the field of ecology to make sense of recent changes to the structure of techno-scientific innovation in the US.

The first, from 2023, looked back at the roots of our post-WWII techno-scientific infrastructure and suggested that a great shift was imminent: all that was needed was a pulse perturbation to kick it off.

The second, from earlier this year, looked at the Trump Administration’s evolving techno-scientific policies - specifically his proposed cap on NIH indirects - and argued that a pulse perturbation was underway.

This post follows the same arc as the first two, but looks to the future. I offer a blueprint for Directed Innovation Institutes - a type of non-profit “startup” that advances university-derived technologies in partnership with industry and private foundations.

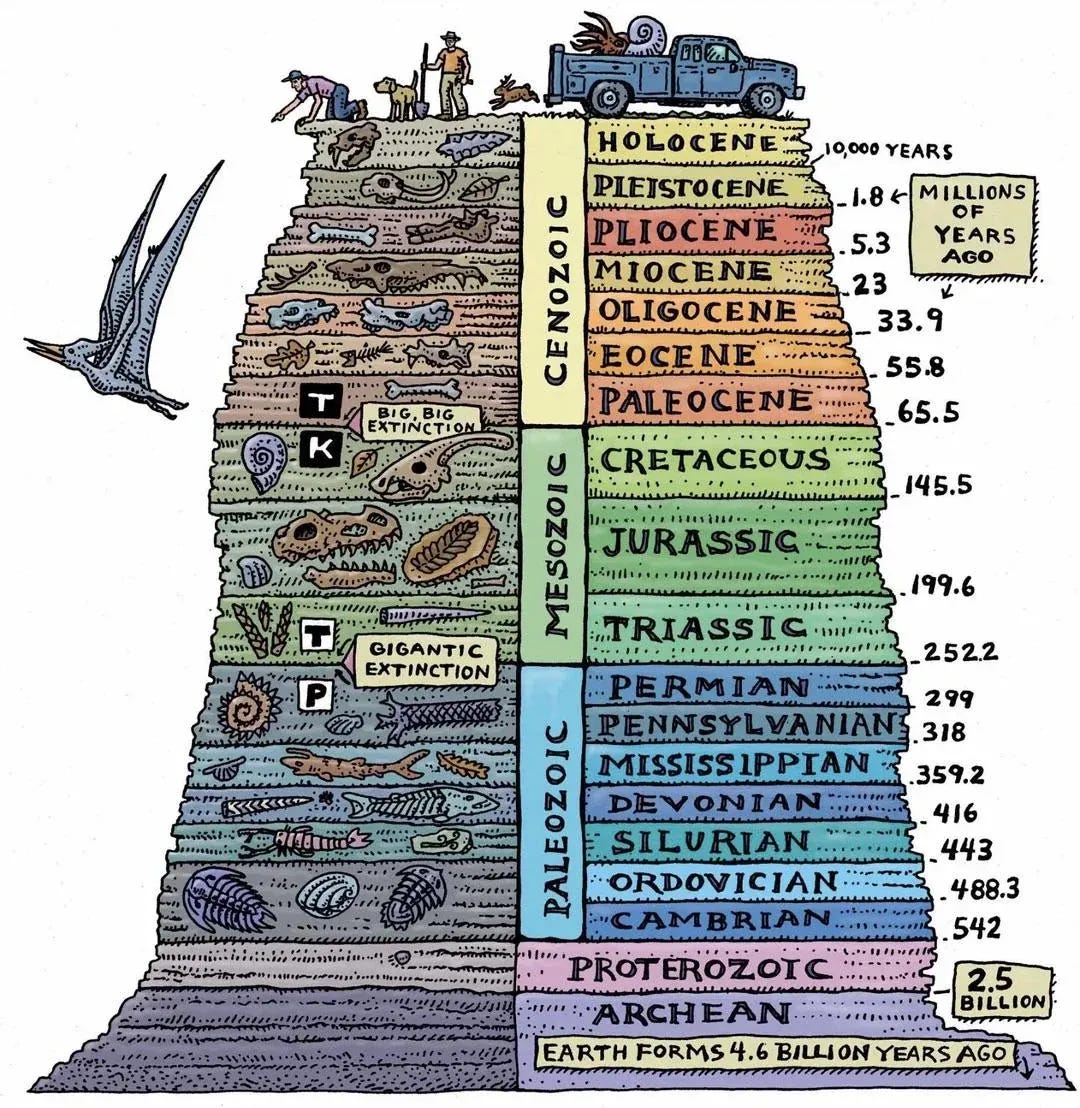

Roughly 66 million years ago, a large rock charted a course from deep space toward an era-defining collision with planet Earth. When it struck just offshore of the village of Chicxulub on today’s Yucatán Peninsula, the asteroid released energy equivalent to about 100 trillion tons of TNT, liquefied around 25 trillion tons of rock, heaved the ocean into waves over 300 feet high, rained molten debris across the globe, filled the skies with ash for 10 years, and initiated the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event, wiping out about three-quarters of all plant and animal species and upending ecosystems worldwide.

That single space rock abruptly ended the Mesozoic Era - the age of the dinosaurs - and inaugurated the Cenozoic: the age of birds, mammals, a few eerily unchanged holdovers like horseshoe crabs, and us.

Ecological history is one of punctuated equilibrium. Periods of relative stability are inevitably interrupted by disturbances: asteroid strikes, ice ages, catastrophic fires, world wars - what ecologists call pulse perturbations - that throw the existing order out of balance. Old structures collapse; new ecological niches open; and once marginal species expand and diversify until a new equilibrium emerges.

In evolutionary biology, this diversification phase is know as adaptive radiation: species branch rapidly into new forms and phenotypes to exploit a changed environment. The same process plays out in human history - cultural, political, techno-scientific - though on shorter time horizons.

Eras of Technoscience

One could split the last eighty years of techno-scientific history into two distinct, forty-year periods. The first began with World War II, a pulse perturbation of such magnitude that it still anchors the self-conception of many cultures. In its afternmath arose many of our most consequential techno-scientific institutions: the NIH and NSF, the modern research university, the national lab system, agencies like NASA and DARPA, and the great corporate R&D labs - Bell Laboratories foremost among them. I call this forty-year, post-war period the Era of Centralized Innovation.

The second began with a far quieter catalyst: the 1980 passage of the Bayh-Dole Act, which reshaped how the baton of scientific research is handed from universities to industry. In my reading of history, Bayh-Dole marked the birth of the startup-venture-capital paradigm for commercializing science, and, with it, modern biotech and pharma. I call the forty-year post-Bayh-Dole period the Era of Unbundled Innovation.

The third era began in early 2025, when President Trump announced his administrationa’s intent to cap NIH indirect fees - the lifeblood of modern research universities - at 15 percent, down from 40 to 50. This move immediately stripped roughly $5 billion from university balance sheets and, combined with other recent policies in the same vein, threatens their current mode of existence. Whether those actions were a deliberate attempt to reshape American science, or simply a convenient way to pressure political opponents (I suspect both), what can’t be denied is that they achieved both effects.

The Trump administration is like an asteroid strike, or a forest fire burning down the post-WWII techno-scientific order. Yet in the months since January, we’ve begun to see the first signs - some of them quite promising - of adaptive radiation. As in biological adaptive radiation, this has involved taking forms that arose in previous eras - like wings and warm blood - and adapting them to suit new ecological conditions.1

The Era of Centralized Innovation (1940-1980)

World War II unambiguously ushered in an era of big, top-down, coordinated innovation. Great-power rivalries focused the attention of entire nations on existential challenges with tangible, immediate consequences.

The existential threat of the war years meant that academic scientists around the world were effectively conscripted to support their country’s military in developing technologies for war. Those expelled by their country of origin, including, decisively, most of continental Europe’s Jewish scientists, took up positions in the US or UK. In all but a few cases, they were quickly integrated into the military-scientific machine. Never-before-seen sums of money were lavished on scientists and engineers. In return the government was to decide, at least at a high level, how it was spent. Vannevar Bush, then the Director of the US Office of Scientific Research and Development (superseded by the NSF) proposed that the then unprecedented government support of academic science be continued into the post-war era.

Institutions that are now seen as bedrocks of innovation in the US and the world - MIT, Harvard, Stanford, UC Berkeley - solidified these positions by hosting massive military research programs on their campuses, in effect calling “dibs” on the best and brightest scientists and engineers available. MIT’s Rad Lab, Harvard’s Computation Lab, Berkeley’s Radiation Lab, and later, MIT’s Semi-Automatic Ground Environment air defense system (SAGE), employed hundreds of scientists each and became central to the inventions of RADAR, SONAR, nuclear energy, and computers, as well as a host of new materials and devices.

The end of war in 1945 meant the prospect of the government winding down support for research to pre-war levels. Universities across the country would be left with empty buildings and scientists of all stripes left without jobs. No doubt already hearing rumblings of this from his perch in Washington, DC, Vannevar Bush penned a now-famous letter to President Roosevelt arguing that government support for science should not be diminished after the war, but simply re-oriented toward fighting a new “war of science against disease.” Bush’s proposal, though not implemented in its details, laid the conceptual groundwork for the centrality of the NSF and NIH in postwar research. Both his letter, since published as “Science, the Endless Frontier”, and Roosevelt’s response merit a read by anyone interested in the history of scientific research.

To this day, the majority of basic research in the US is conducted by professors and graduate students on university campuses, funded in large part by government agencies. Roosevelt’s initial vision of a “war of science against disease” also persists; more than half of all government funding for research remains dedicated to advancing human health.

One of the most consequential legacies of the Vannevar Bush system was how it shifted research funding from private to public hands, stabilizing the soil for enduring innovation ecosystems to form around agencies like NASA and in cities with major research universities. Even the great R&D Labs were, in a sense, publicly subsidized: AT&T’s government-sanctioned monopoly generated the excess profits that sustained it’s R&D engine.2

From a systems-level perspective, the Centralized Innovation paradigm works roughly as follows:

It begins with a techno-scientific “mega project” with unimpeachable institutional support: We are going to build a bomb to end the war. We are going to the moon to beat the Soviets. We are going to connect the nation by telephone.

The project is decomposed into a hierarchy of technical problems, each translated into a specification. Or what in pharma is called a Target Product Profile (TPP).

The path from spec to product is centrally directed and sustained by stable, single-source funding, allowing invention and discovery to iterate under one roof.

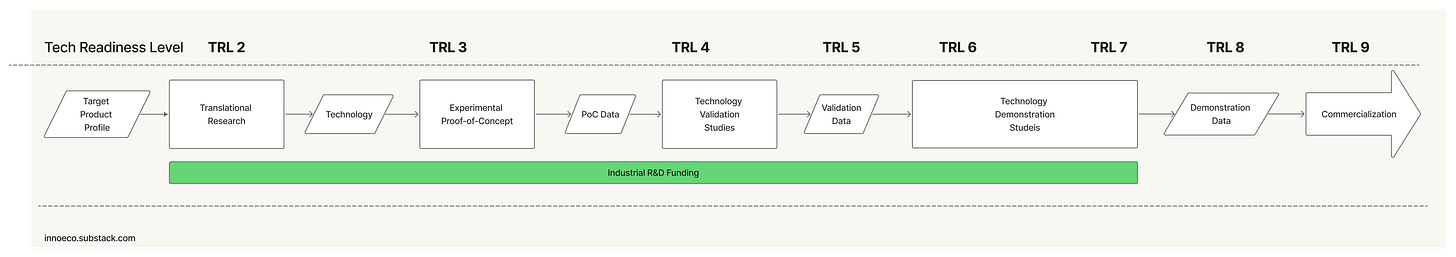

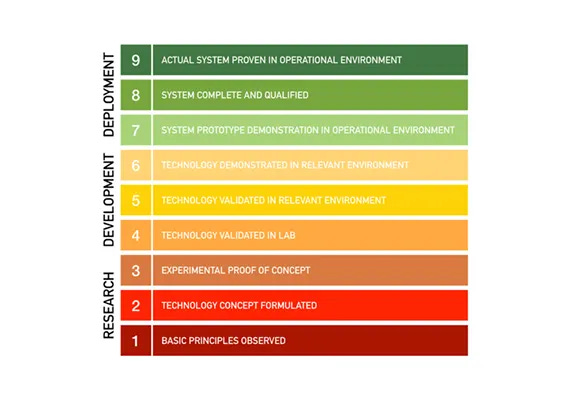

The project is advanced through sequential stages of Technology Readiness3, culminating in a finished product that satisfies the spec or TPP.

The resulting product is commercialized by the same organization that funded its development: either directly or as a component of a larger system.

For this model to work well, several conditions must be met:

A moment of extraordinary social or organizational cohesion driven by crisis, vision, or both.

A decision made with the authority and will to underwrite a large, sustained financial commitment to a speculative project.

A scientific opportunity suited to this model - for example, a foundational discovery whose translational potential is evident, even if the road to get there isn’t entirely clear.

By the late 1960s, these conditions ceased to pertain. The social compact binding scientists, industry, and government around shared national projects began to loosen; The space race had been won and the optimism of the post-ware years gave way to disillusionment. Into that drift floated the economic logic of “shareholder value”, which replaced that of “patient capital”. Private R&D Labs that once operated as semi-public institutions - Bell Labs, DuPont Central Research - were now forced to justify themselves quarter by quarter. By the close of the 1970s, the architecture of centralized innovation still stood, but the idea that techno-scientific innovation should be unbundled - pursued by smaller, faster, more flexible actors, had already taken root.

The Era of Unbundled Innovation (1980 to Present)

The Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, which granted universities ownership of federally funded IP, largely codified the shift from an era of Centralized Innovation to one of Unbundled Innovation. Where the postwar era emphasized scale, hierarchy, and coordination, this new era prized modularity, specialization, and speed.

The Bayh-Dole Inflection

After World War II, federal agencies took center stage in funding university research and become some of the largest patent holders in the country. Inventions created with federal funds were, by default, government property, and agencies rarely granted exclusivity. Private firms were reluctant to invest when competitors could license on equal terms. By the late 1970s, the government held more than 28,000 university-derived patents; fewer than 4 percent were licensed.

Bayh-Dole solved the impasse by transferring ownership from the funding agency to the host institution and by obligating universities to pursue commercialization. The result was an expansion of university patenting and the creation of tech-transfer offices. Inventions that once sat on government shelves became available for exclusive licenses. Entire industries, biotech foremost, grew from this new alignment of incentives.

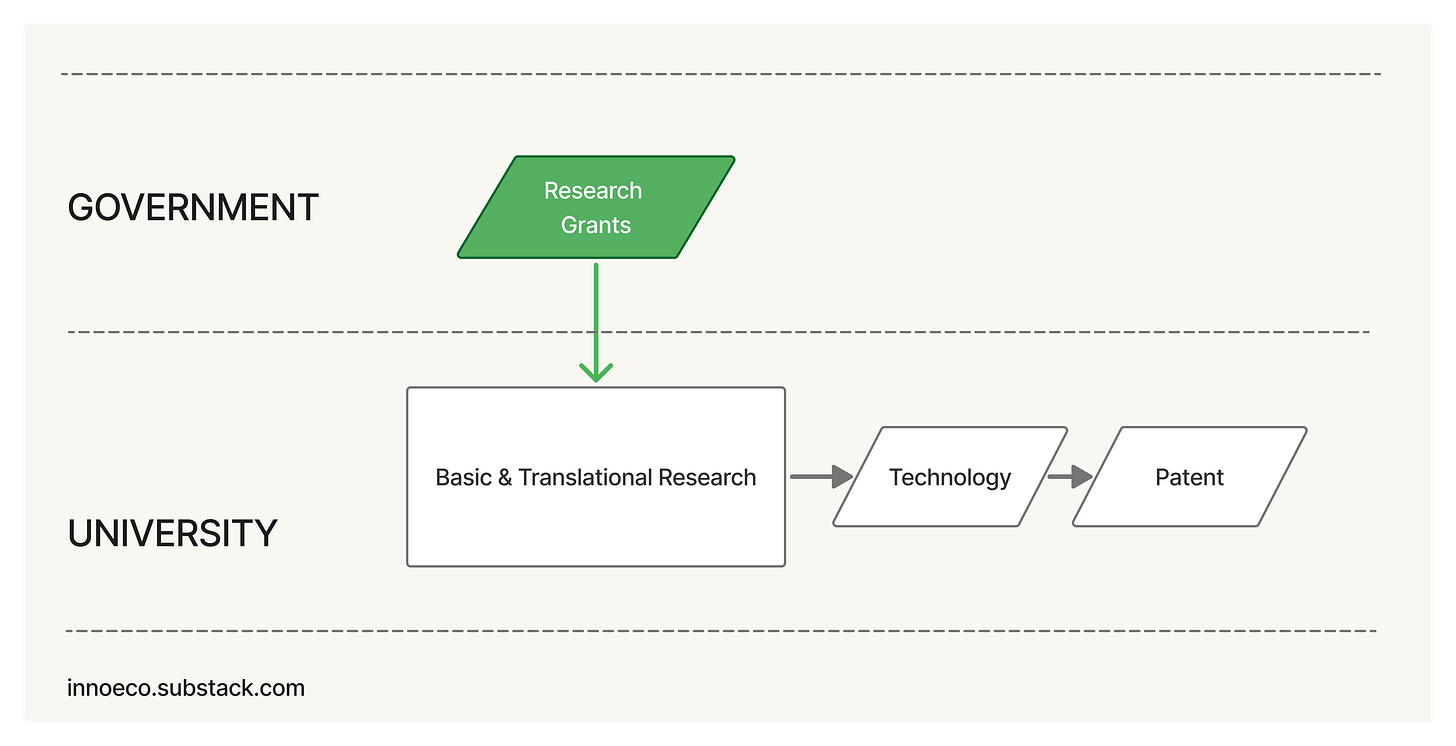

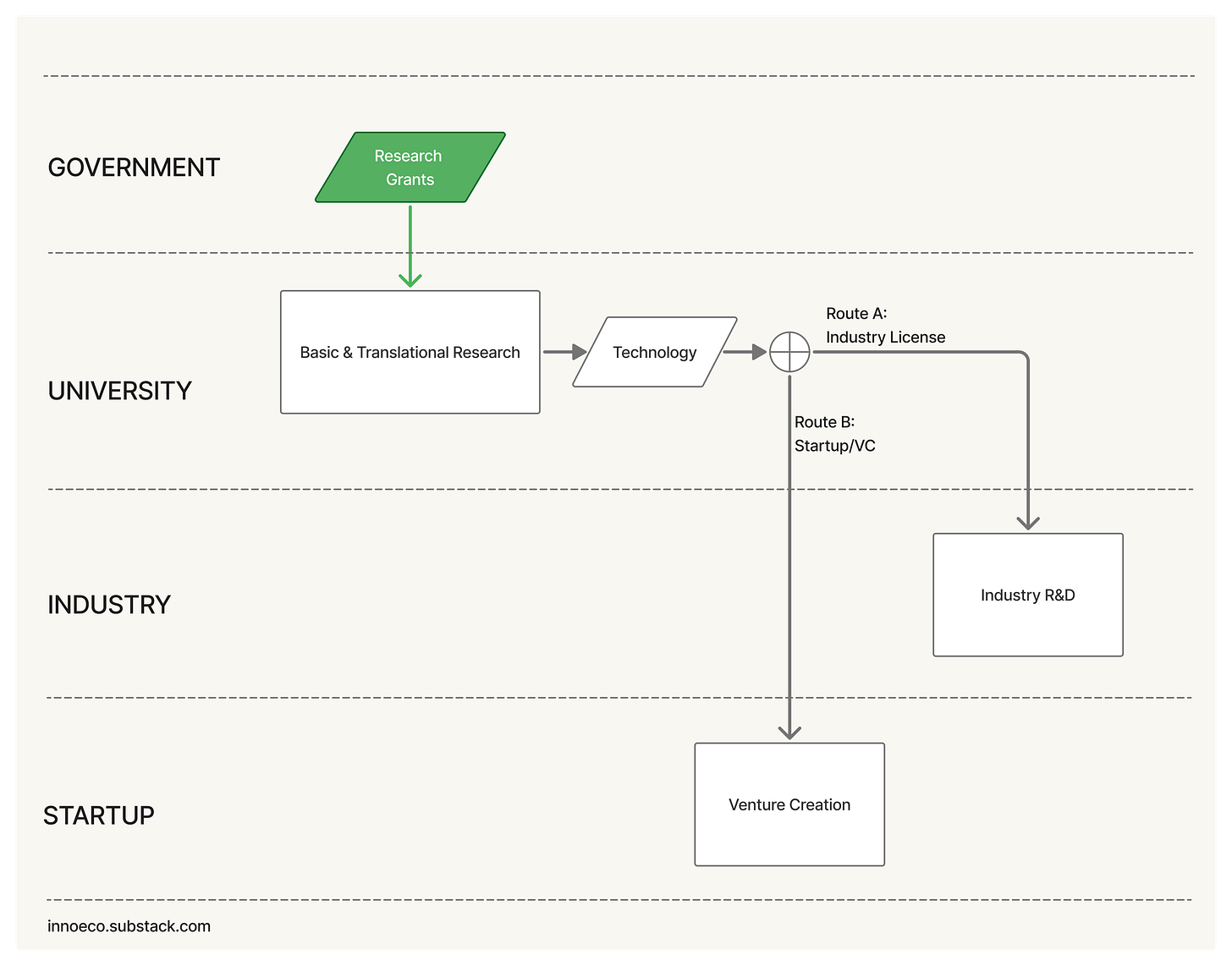

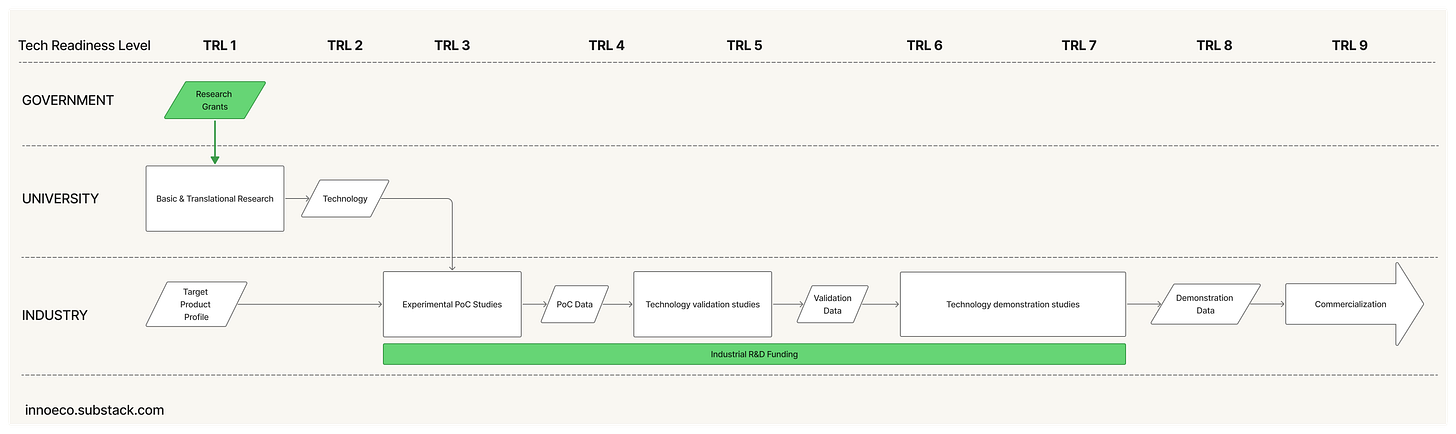

The relay race model of commercialization

The system began to resemble a relay race. A government grant funds curiosity in a university lab → Some discoveries show application potential: a new therapeutic target, a novel polymer, a diagnostic method → The researcher files an invention disclosure → The university files a patent. And so on, until the baton passes down one of two tracks: 1) license to an established company, or 2) form a startup. Both paths share an underlying logic: risk moves sequentially from public to private hands. From highly uncertain exploration to commercially disciplined application.

The industry license-paradigm

In the first scenario, a company licenses the university technology and absorbs it into its own R&D organiation. The steps are straightforward: negotiate license terms, transfer the underlying know-how, absorb it into an internal team, and fund it internally from Proof of Concept through Demonstration as an R&D expense until it matures into a product.

At its best, this model aligns the technology with a validated market need, leverages company-scale resources, and insulates projects from capital-market shocks. Many therapeutics breakthroughs of the 1980s and 1990s - recombinant proteins, monoclonal antibodies - emerged from such partnership between academia and Big Pharma.

For this model to work well, a few conditions are important:

A macro environment that rewards long-term R&D investment rather than short-term financial optimization.

An ecosystem of firms able to absorb and advance external innovation: scientifically sophisticated, organizationally focused, and confident in their internal R&D capabilities.

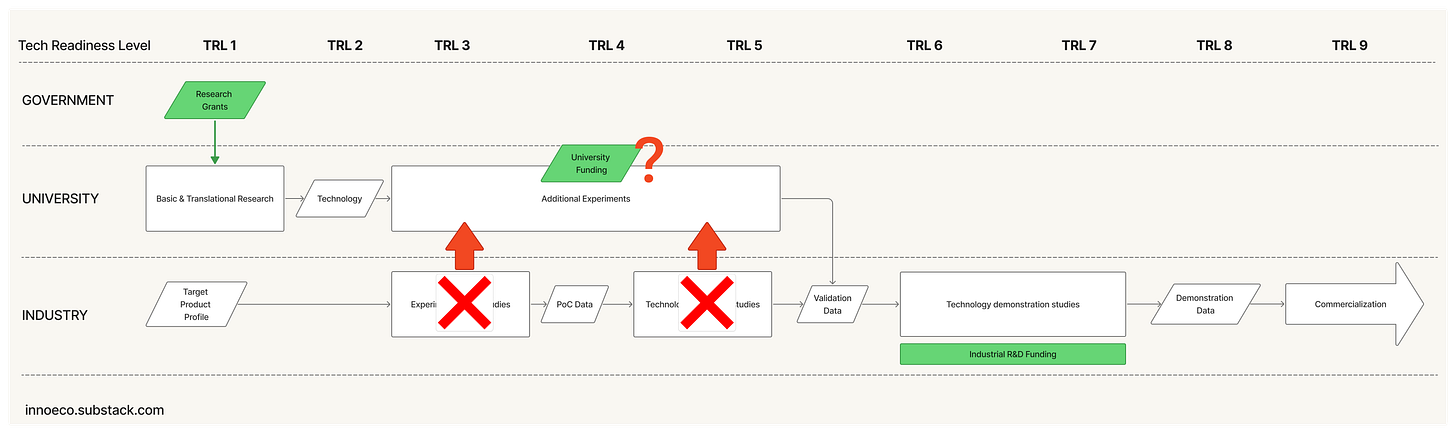

Over time, these conditions have eroded. Under financial pressures, firms tend to externalize more of their early-stage R&D pipelines, widening the gap between what universities can de-risk and the minimum viable dataset” that corporations expect. Some universities have launched proof-of-concept funds or “killer experiment”4 programs to bridge the gap but many lack the resources to do this comprehensively. An increasing shelf of promising inventions fall into this widening gap: too applied for academia, too early for industry.

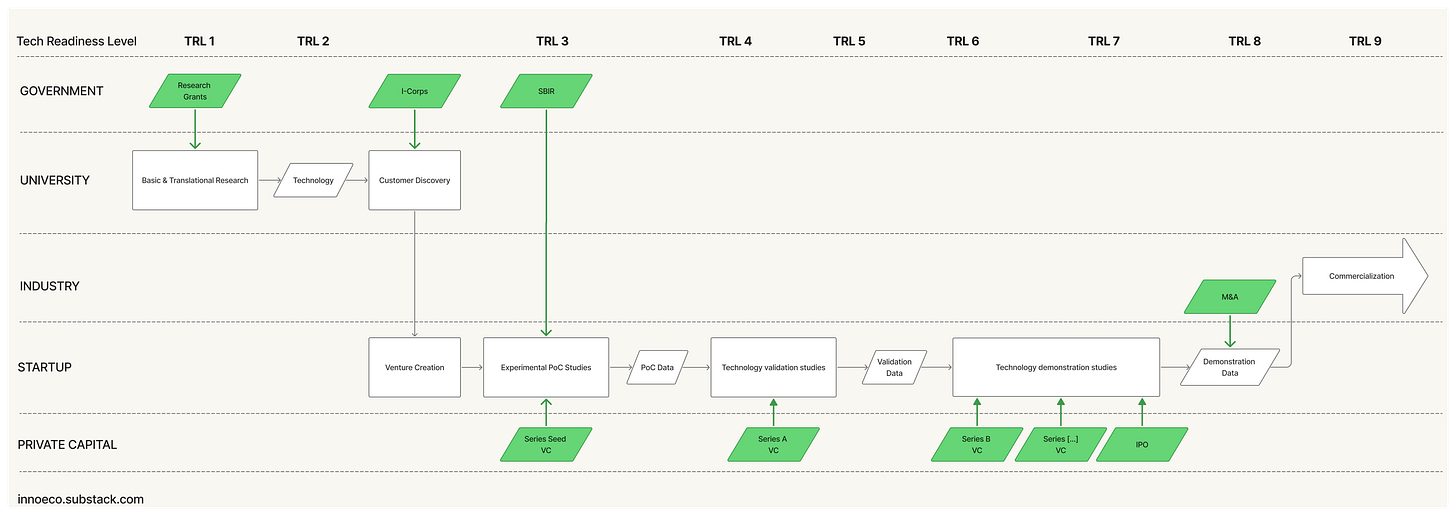

The startup / venture capital paradigm

Into that gap comes the venture creation model. Instead of licensing directly to a corporation, universities form startups around their discoveries and seed them with venture capital. Over time, this has become the default in many places: assemble a founding team → secure an exclusive license → raise a seed round → retire key scientific risks → raise a Series A → […] → exit via an acquisition or IPO. This is an exciting, dynamic model, and it’s where I’ve spent the last ten-plus years of my career. (For a deeper treatment, read my essay here.)

At its best, this model democratizes innovation. Small teams can pursue big ideas outside industry and academia. Startups align incentives tightly: founders and investors share both risk and reward. They move at speeds large organizations rarely match. And venture capital provides a parallel governance structure: milestones replace fixed budgets, and the market becomes the arbiter of progress. For nearly several decades, a self-reinforcing cycle has powered the system: low interest rates draw institutional capital into venture funds; those funds seed new companies; successful exits return liquidity to investors; and the cycle repeats. A number of era-defining companies resulted: from early pioneers like Genentech, Amgen, and Biogen, to second-wave successes such as Gilead, Vertex, and Regeneron, and more recent platform biotechs like Moderna, Ginkgo Bioworks, and CRISPR Therapeutics.

But this model also carries constraints and sensitivities:

Cheap capital: interest rates low enough to push investors toward risk assets.

Experienced startup CXOs: ideally people with a few companies under their belts.

Predictable regulation: confidence that approvals and reimbursement will follow success.

Open exit markets: IP and M&A pathways that recycle capital back into the ecosystem.

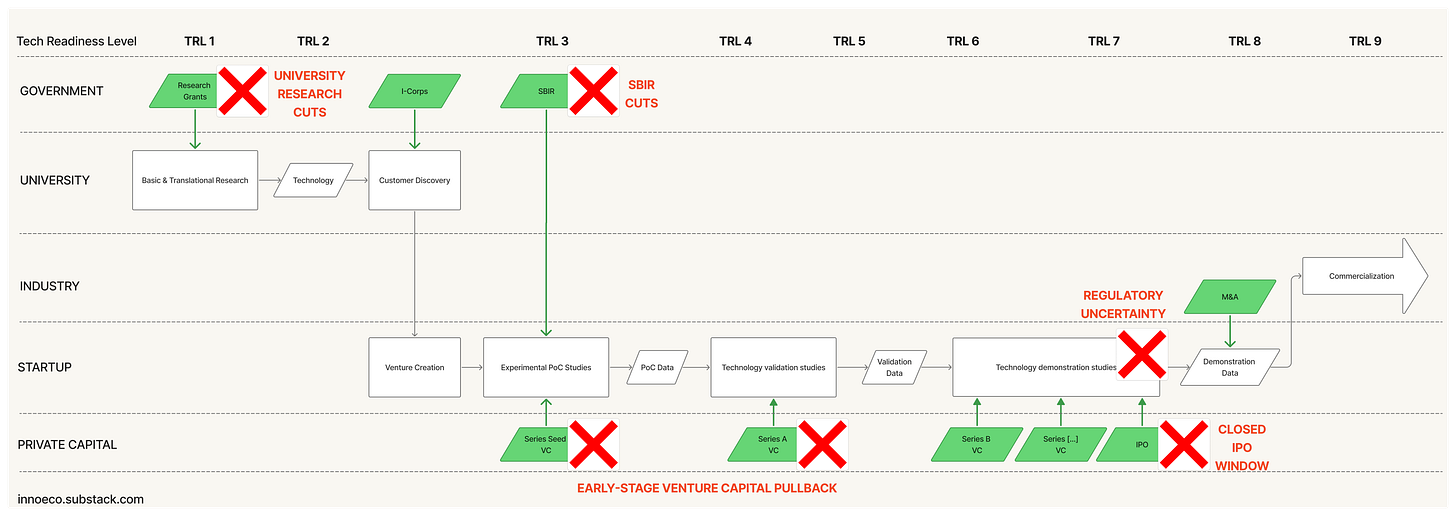

Since 2021, these conditions have faltered. Higher interest rates have caused institutional investors to pull back from venture or reallocate toward AI. The IPO window has stayed largely closed. Regulatory signals are chaotic. And while university labs remain productive, funding is at risk and downstream translational machinery has seized up. Combined this with the Trump administration’s intent to upend research universities, the NIH, and the FDA - the pillars of the old order - it seems obvious that we have tipped into a new paradigm.

A New Era of Directed Innovation (2025→)

So, if we are entering into a new era in the history of technoscience, what comes next? What if we could recover the best features of the Centralized Innovation era, combine them with the best features of the outgoing Unbundled Innovation era, and make the resulting model more resilient to shocks? I think we can.

To survive and thrive in this new environment, future models of technoscience will need to exhibit six characteristics:

Financial flexibility - When ecosystems shift, species that depend on a single food source disappear. Resilient technoscience organizations must be financially omnivorous. In this new era, there a five food groups of funding: government, philanthropy, corporate, venture capital, and earned revenue. A balanced diet is essential.

Problem Pull (vs. Discovery Push) - A hallmark of the Centralized era was the centrality of the problem itself in guiding R&D. Shockley’s semiconductor work at Bell Labs, for example, looked like basic science but everyone understood the objective: replace the vacuum tube with a solid-state equivalent. When innovation unbundled into today’s relay model, that signal weakened. NSF’s I-Corps programs tried to restore it, but with new innovation-mapping tools and AI systems like Stargaze, we can now reintroduce problem orientation earlier, and at scale.

Early Problem-Owner Investment - Nearly every successful science-based startup is eventually acquired by an incumbent. Viewed this way, the VC / startup ecosystem operates as a distributed form of outsourced corporate R&D. Yet in the handoffs, the voice of the problem-owner often fades. Involving corporations or foundations - the ultimate solution implementers - as early investors, keeps translational focus intact. The risk of corporate capture is real but outweighed by the benefits of alignment.

Keep Innovation External - One of the strengths of the Unbundled era was its separation from both corporate bureaucracy and academic inertia. Anyone who has left either to join a startup knows how much faster it can move. This externalization also creates financial flexibility: corporations can maintain exposure to long-term R&D without shouldering its costs internally.

Directed, Asset-Focused Investment - The Centralized era excelled at coordinating large-scale projects—moonshots funded with patient, mission-driven capital. As innovation fragmented in the 1980s, that capacity eroded. The Focused Research Organization (FRO) model, developed by Convergent Research, revives that logic at a meso scale: roughly $50M portfolios aimed at solving discrete “essential technologies” that fall between the scope of a single lab and a national program.

Leverage Existing Infrastructure - Universities, venture studios, and hybrid institutes already hold immense technical and translational infrastructure. The most efficient new models won’t rebuild it, but determine ways to harness it. DRIVE at Emory, for example, integrates with Emory’s cores, IP systems, and clinical networks while maintaining autonomy.

Exemplars of Directed Innovation

Several organizations already exemplify this emerging pattern:

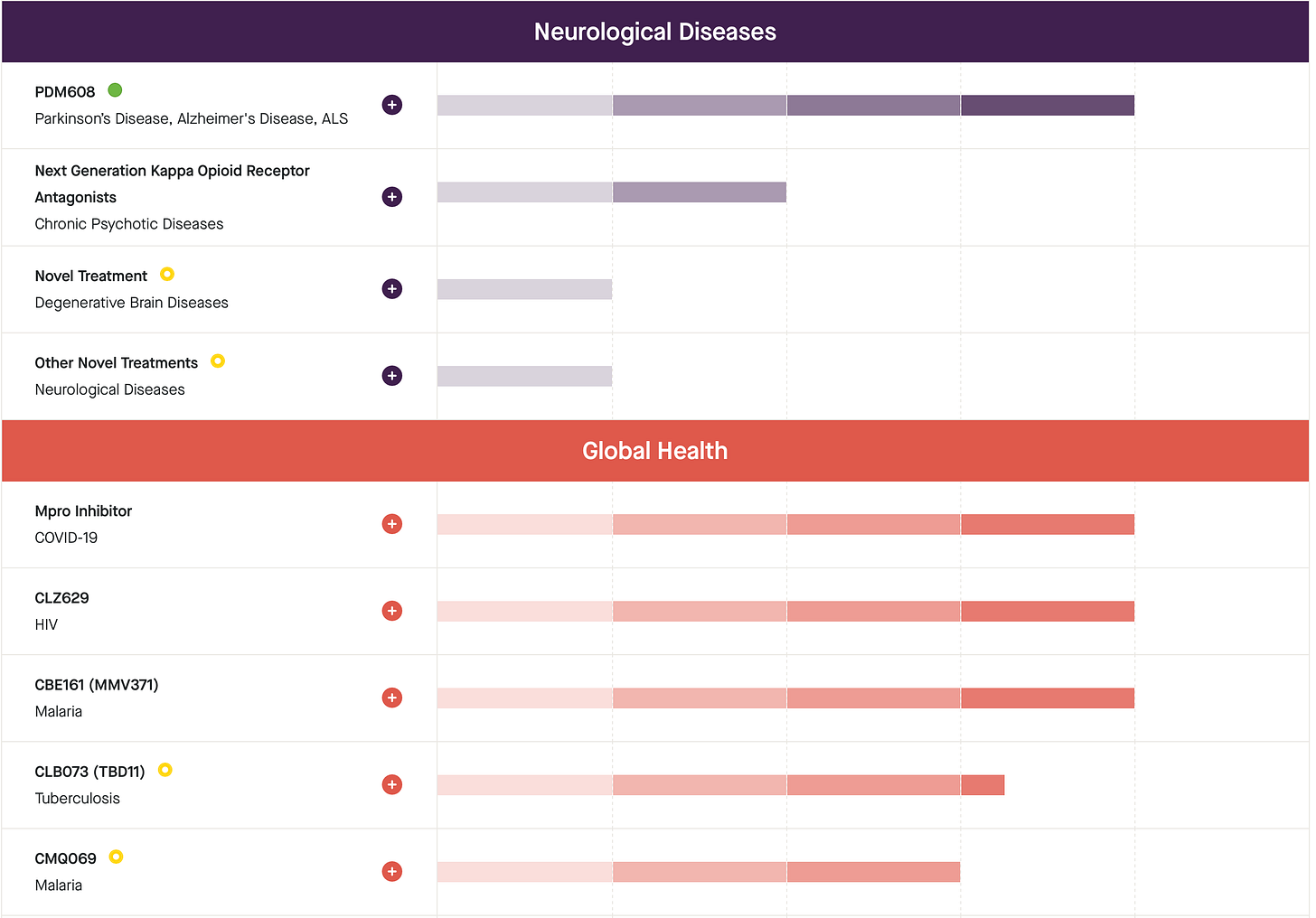

Calibr @ Scripps: Founded as a translational research institute parallel to Scripps, Calibr pioneered an asset-based portfolio model in which each program advances through partnerships with a different sponsor—pharma, foundation, or public agency—spreading risk across a diversified pipeline.

Blackbird Labs @ Johns Hopkins: Led by Calibr alumnus Matt Tremblay, Blackbird adapts that playbook to the Johns Hopkins ecosystem, focusing on high-potential discoveries that are too applied for NIH grants yet too early for venture capital.

DRIVE @ Emory: Co-founded by Emory’s drug-discovery leadership, DRIVE serves as Emory’s translational arm while remaining legally distinct. It leverages university infrastructure but operates with the agility of a company, reinvesting returns into new programs.

Convergent Research (FROs): A distributed network of project-specific, non-profit R&D entities built to tackle “essential technologies” such as protein design platforms and advanced manufacturing—each with a defined deliverable and sunset plan.

Directed Innovation Institutes (DII)

Together, these point to a generalizable organizational archetype I call Directed Innovation. It’s focused like Centralized Innovation, agile like Unbundled Innovation, and ecologically resilient in its mix of funding, governance, and structure.

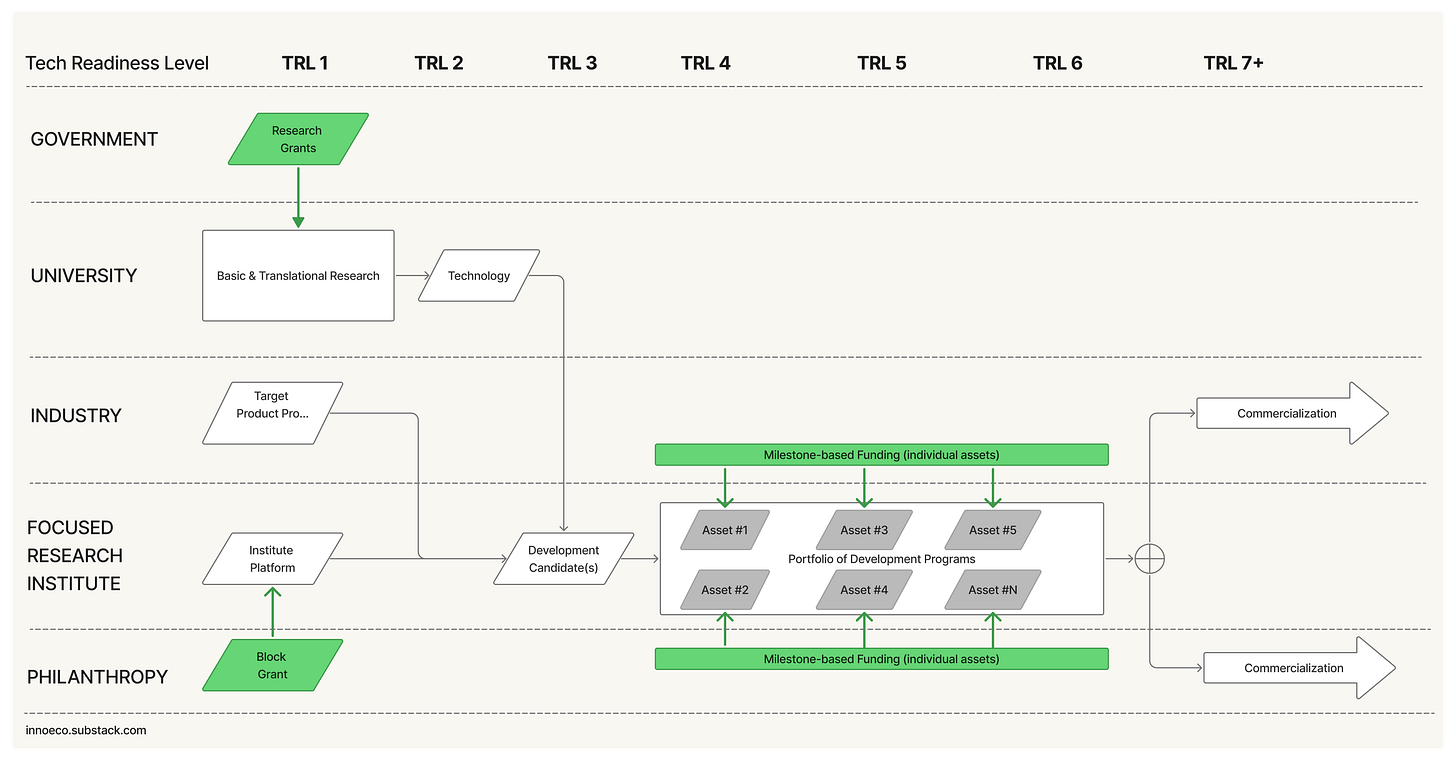

Here’s a schematic of what Directed Innovation Institute might look like:

At the core of a DII is a portfolio of assets, or development programs, at different stages of development. At first, a portfolio is directed at either a single technology / modality with 3 to 5 applications (e.g. targets) OR a single application (e.g. a therapeutic area or biological target) with 3 to 5 modalities. Over time, new portfolios could be added à la Calibr, perhaps one new portfolio every five to ten years. But this isn’t strictly necessary - a single modality organization would be more than sustainable.

At steady state, imagine an organization with ~20 employees on the low end, and ~150 on the high-end. Each portfolio has its own technical development team, an asset lead dedicated to each asset, and one or two functional groups dedicated to specific key capabilities (e.g. a biobank, data model, model context protocol, synthesis core, gold-standard in vivo model, …). These functional capabilities could be developed in house, like Calibr’s Novel DNA encoded library, or accessed via exclusive partnership, like DRIVE’s Emory-hosted labs, or both.

Funding

A DII organization is seeded via a founding block grant, which covers the initial team and infrastructure build, asset selection, and enough dry-powder to advance 3+ assets from TRL 2 to TRL 4+. Mechanically, I imagine the block grant working a lot like Watney’s proposed X-Labs funding vehicle, but underwritten by a foundation, corporation, or donor-advised fund.

Each DII asset is partnered from the earliest possible moment with a corporate, philanthropic, or government sponsor, using a standard biobucks-style agreement with an upfront payment, milestone-based investments, royalties, success payments, and acquisition options. After the first five assets, new assets are only added if a partner is identified. Over time, substantially all assets should be partnered; this is the desired end state. As the portfolio generates returns, they are recycled back into the top-level organization

At five years, success for a DII would look a lot like DRIVE. A single modality with one successfully commercialized asset. At ten years, success would look a lot like Calibr: A portfolio of three to five focus areas, each with three to five assets; and an ecosystem of industry/foundation partners, each with multiple sponsorships.

How do Directed Innovation Institutes differ from existing models?

Venture Capital: DIIs preserve the diversification, and milestone-based funding of VC portfolios. But unlike the typical VC portfolio, each asset is funded by a different corporation or foundation, spreading out financing risk and ensuring pipeline alignment. Also unlike VC, this model can sustain assets with a more indirect or medium-range return profile.

Focused Research Organizations: Unlike FROs, this model focuses on discrete assets with a clear line to translational potential. While current FROs will remain better suited toward more speculative, meso-scale moonshots, DIIs will be better suited toward assets with clear industry tie-ins.

Corporate R&D: Unlike Corporate R&D, this model retains an External Innovation posture. It benefits from the direction of industry (via TPPs for each asset), but maintains the benefits of startup culture, autonomy, and speed.

Like birds or mammals after the K-Pg extinction event, the DII model takes the most valuable features from past eras, and re-imagines how they might be utilized to achieve new functions in our rapidly changing environment.

Next

Every major city could support at least one DII per several million residents. Over the coming months, I’ll be developing a concrete blueprint for one in my home city of Chicago. I hope to write more about that, here, along the way. If you’re interested in collaborating, whether in Chicago or elsewhere - drop me a line in the comments below!

Leading this new wave are organizations like the Institute for Progress (see their Techno-Industrial Playbook and Launch Sequence), Convergent Research (publisher of the Essential Technology newsletter), the NobleReach Foundation, and even the U.S. Congress’s National Security Commission on Emerging Biotechnology (see their final report, especially Chapter 2).

(For a sharp overview, see James Phillips’s New Technoscience Laboratory Designs; for a deeper narrative, John Gertner’s The Idea Factory is a personal favorite.)

TRLs were developed by NASA in the 1970s and have been used by the US government and the private sector ever since. The Technology Readiness Assessment Handbook is maintained by the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and engineering. Here’s the high-level visual rubric:

Jacob Johnson at Innovosource publishes a yearly report on the state of Gap Funds across the US, called Mind the Gap.

Steve - one side effect of Bayh Dole was also the loss of incentives for universities to work on problems that could not make money. It has created a new gap for solving “smaller” or less easily monetized problem sets. I think this is one of many challenges accumulating into a growing distrust of science.

Hello Steve, I'd love to talk with you more about this. I edit www.issues.org and this connects with, and extends, some of the things we've been publishing over the past year. lmargonelli@issues.org. Lisa